|

|

|

Jimmy Nalls:

Making Music to Live By

by John Lynskey

|

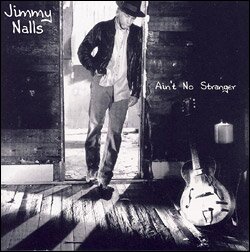

Jimmy Nalls made his mark in the '70s with his stinging lead guitar work for the seminal band Sea Level, and as a top session player in Macon during the height of Southern rock. Musically, Jimmy is back, with an absolutely stellar album, Ain't No Stranger; personally, he is facing the challenge of his life as he battles Parkinson's disease, which he was diagnosed with in 1995. Jimmy, always upbeat and honest, talked openly with HTN about the dichotomy of life, and how the disease that threatens him sparked his return to the recording studio. It is an interview that is very human and personable in content—sometimes sad, sometimes funny, but always containing the dignity and class that is Jimmy Nalls Jimmy Nalls made his mark in the '70s with his stinging lead guitar work for the seminal band Sea Level, and as a top session player in Macon during the height of Southern rock. Musically, Jimmy is back, with an absolutely stellar album, Ain't No Stranger; personally, he is facing the challenge of his life as he battles Parkinson's disease, which he was diagnosed with in 1995. Jimmy, always upbeat and honest, talked openly with HTN about the dichotomy of life, and how the disease that threatens him sparked his return to the recording studio. It is an interview that is very human and personable in content—sometimes sad, sometimes funny, but always containing the dignity and class that is Jimmy Nalls

HTN: Jimmy, Ain't No Stranger is flat-out great. Tremendous, absolutely tremendous.

JN: God bless you, man—that's awful nice. You know, there's been nothing but positive comments about it—I sort of got my seat belts fastened, because somebody's bound to blast me, but so far it hasn't happened. Everybody's been so nice about how it turned out—I'm just tickled.

With just cause, Jimmy. Relate for us if you will the factors that led up to the recording of Ain't No Stranger.

Well, I wish it was all positive, but—and some of your readers may not be aware of this—I came down with Parkinson's disease. It's the same thing that Muhammad Ali and Michael J. Fox have got, and it's progressive. I'm doing fine, and I'm fighting it with everything I've got. I'm taking yoga classes, still jogging as much as I can, walking, working out with my weight machine—I'm trying to be a moving target. The last few years have been spent really battling that—and writing. I've begun to focus a lot more on the writing aspect of my music, because I've had to give up the road—at least for now—until we get this thing beat. There are always arenas that are working very hard to cure this thing. I'm not counting myself out as far as being a gunslinger and getting back out and doing it on stage again, because I really miss that—it was fun. In order to fill that gap, I've begun to write a little bit more, produce, and try to stay busy that way. Anyway, I did some projects for MLR Records, which is mostly a blues-based record label here in Nashville. They were familiar with my background, and I contributed a song or two to some projects that they were doing. The things that really kicked it off were the Blues Co-Op project in 1997, and then Rick Moore's album in 1998, which I co-produced. Long story short—MRL said to me, "Man, we know your background, and we know that you still got a lot of people out there that love you and would like to know what you've been up to lately. Why don't you consider doing a solo project while you still have the goods and the time?" I told them, "Well, that's very nice—let me think about it." I thought about it for a couple of months, continued to write some more, and decided last fall with my good friend Phil Dillon—who co-produced the project—that we would see what we could muster up with this. We agreed with MRL to go ahead with the project, and started pre-production last fall. I had a whole bunch of songs that I always wanted to do, and we quietly went to work. I didn't have any idea how this thing was going to turn out, but MRL told me, "Man, you got carte blanche—whoever you want to use, within reason—do it." Phil and I came up with a bombastic list of players for this thing—everybody we loved—and pretty much everyone that we asked ended up playing on it. We very quietly did the album over the winter, and as it began to take shape, we then started to let the cat out of the bag. I honestly didn't know how it was going to turn out—or if I could even finish it. With this thing, some days are better than others, and a couple of times unfortunately I had to say, "Look—let's call it early. I'm running a little slow today." We just took our time, did it at my pace—Phil was very patient, very gracious, and walked me through it. I could have produced it myself, but I really wanted somebody to kind of nudge me along. It turned out pretty good, and long about April, we started saying, "Well, we've been working on this little project here," and everybody says, "No kidding! Let's hear it."

I love the New Orleans, down-in-the-swamp feel the whole album has—it's got the gris-gris all over it. What made you go with that theme? I love the New Orleans, down-in-the-swamp feel the whole album has—it's got the gris-gris all over it. What made you go with that theme?

Well, we can thank Mac Rebennack for that. The schooling that Chuck Leavell and I got from that man—we were in his band for less than a year, but that was like going to a four-year college. I've said that through the years, and will continue to say that. It was an incredibly educational and fun thing to do, although at the time he scared the hell out of all of us! [Laughs] He was this big looming figure—bigger than life itself—yet he was very accessible, and he would talk to you. He had a certain thing about him that was just Mac, you know? He has softened through the years, he's not quite as scary—or maybe it's just because I've gotten older. [Laughs] I mean, when you're 19 or 20 years old and you're playing with Dr. John, the Night Tripper, and you know he's listening to every note you play—wow! I'll tell you a funny story. The band consisted of Charlie Hayward, Paul Hornsby, Chuck, myself, Lou Mullenix, and Bill Stewart, and we were playing with Alex Taylor, until he took some time off and went back to Martha's Vineyard. Well, we knew that Mac was moving to Macon, and that he needed a band. He was told that there was a ready-made band waiting for him in town, so we knew about two weeks in advance that we were going to playing with Mac. Man, we bought every Dr. John record there was, and we thought we knew how to play second line and that we really got it down. We practiced and practiced, until the day Dr. John sauntered in with his entourage. He listened to us for a song or two, and he says, "Well, y'all sound pretty good, but I'm going to have to show ya how to play second line!" [Laughs] This was after two weeks of flat-out gettin' it, too! He affected all of us—it comes out in Chuck's playing, and he influenced me tremendously.

You're signature guitar work is everywhere on this album. You're style is so distinctive—you don't waste a note, every lick is precise, and your timing is impeccable.

Well, thank you so much, but I'll tell you what, I've had to slow down and leave a lot more holes lately.

Well, it still sounds like Jimmy Nalls—there's not a wasted lick, and sometimes what you're not playing is more important than a long string of notes anyway.

God bless you for saying that—I've said that in past interviews, that very statement. What you don't play makes all the difference in the world—and makes what you do play stand out more. I've made that very statement, so it's great that you noticed that on the album.

Your vocals—they are down and dirty, and a perfect match for the music. It was a real pleasant surprise to hear you sing.

Singing is something that I've always done, but I just always wanted to be a guitar player. I enjoyed just getting out there and gun-slinging it—standing on the edge of the stage and trying to scare people. I liked that aspect of being a loaded gun, so singing wasn't all that important. I did sing here at the house a lot with an acoustic guitar, and lately I've begun to sing my own demos. I'd listen, and say to myself, "You know, that don't sound half-bad." I'm not the greatest singer in the world, but it is me, and for what it's worth, let's see if it will fly. About 98% of it is on key [Laughs]—I think it sounds just fine.

The diversity of the tunes on the album is just wonderful—"The Voo Doo in You."

What did you think of that version?

I really liked it—I thought it set the theme of the album perfectly. It's real gritty, and the perfect opening track.

That's always been a favorite of mine—it was on Johnny Jenkins' first record. We use to play it all the time with Alex Taylor.

When it opens like that, it's like, "Whoa." That song makes a statement for sure.

That's what we thought—we wanted to take the old baseball bat and hit 'em up side of the head! As soon as it hits the downbeat of that first chord, we wanted to give everyone an idea of where this thing was headed.

"Down in New Orleans" is Dr. John, "Devil at My Door" is right out of the Delta, "Hey Brother" is pure gospel—I could talk about every track, but is there one tune that is a favorite of yours?

I think the entire CD holds up really well, but a track that is one of my favorites—and strong as hell—is "House of Love." I love that signature lick in there that sets up the song. I didn't write that one—it was written by Rick Moore, along with Will Rhodarmer, who plays harmonica on the album. Will is a world-class harmonica player—I can't talk about this guy enough he is bad to the bone. I also love "The Stroll," because I'm a child of the late '50s, and I really love that particular song, but nobody has covered that. You know, I put the CD away for a month or two, didn't listen to it, and when I pulled it back out, I still thought it sounded great.

As you mentioned earlier, you did assemble an all-star cast of players to contribute to Ain't No Stranger.

Oh yeah. First I called Chuck—I knew his schedule was rather hectic with the Stones' thing—and said, "Look, I'd love for you to play on a couple of songs, if you would," and he told me, "Sure—just send me a DAT." I sent him a DAT, and Chuck nailed it—he really did. We left that little talking at the end of "Ain't No Stranger to the Blues"—that's Chuck, and it's so great. He goes, "Yeah—there's a couple of nice bits on there." Phil and I were laughing hysterically, and the thing is, that was his first pass at it.

That's a hellava first pass.

That's why we left it on there, because Chuck says, "Yeah—there's a couple of nice bits on there," and we're saying, "No shit!" [Laughs] He did a great job on "Down in New Orleans" as well—Chuck is just such an encyclopedia of piano. Then we have Jack Pearson—Jack is another master of the first take. Right out of the chute, he's there. He's begging you, "Please—give me one more!" and you know damn well he just wants to play. He knows he's already got it in the can—two or three times over—he just wants to play! Finally, you just have to say, "All right brother—you're done. Pack it up and go home." [Laughs] Jack is a wonderful human being, and a good friend.

He's all over "It's Mighty Crazy."

That's a tremendous slide solo, isn't it?

Lee Roy Parnell and T. Graham Brown—what they did on "Hey Brother" is tremendously enjoyable.

That tune was a late addition to the record—Phil and Bill Edwards wrote the song sort of about my struggle with Parkinson's disease. They approached me and played the song for me on acoustic guitars, and I told them, "Gee, that's a wonderful song, but I don't want it on my record. This is not a pity party—I want to do a fun, upbeat, in your face, rockin' blues album." They said, "OK," and we let it sit for a couple of days, and then Phil and I talked about it again. He said, "Look man—I can really hear this thing on the record," and he just persisted. He told me, "Let's get T. Graham Brown and someone else to do the vocals," and we were torn between Lee Roy and Delbert McClinton, and eventually we went with Lee Roy, because he is such a good friend and we thought that it would be great to have his slide playing on there. The song was written about my struggle with the disease—and it is a daily struggle—and a lot of bitter-sweet things that you associate with the past, but you can't live there—you got to move on. Anyone can apply their scenario to this song—whether it's a divorce, an illness, or just a bad time in your life—you can insert your situation into this song. Anyway, Lee Roy and T. Graham came over and heard the basic track and the rough vocals, and then they went in and did it together. That was a trip, because they had never sung together, and they really had a good time doing it. I was standing outside, smoking a cigar, just hanging with the guys, while they were listening to the song, and Lee Roy came out and said, "I heard you didn't want the song on the record. You son of a bitch, this song is going on the record!" [Laughs] Lee Roy gave me a hug and told me, "I love you, man—this song is for you." T. Graham and he spent all day doing the vocals, and then we spent another four hours doing his slide part. Lee Roy kept saying, "I want you to play this through me,"—he was just so gracious. We sat nose to nose, and he said, "I want to play what you hear in your head." I just let him fly, and he did such a wonderful job. He'd play for awhile and talk for an hour, he would play some more, and then talk for another hour. We'd laugh and tell a bunch of lies—it was a marvelous day. [Laughs] Lee Roy is a great guy, and that is one thing about this record—it is so humbling. There are so many great folks on it, but they were so gracious and kind. They took their time, they understood the situation, but like I said, it was not a pity party by any means. My situation has changed—all my close friends know about it—and now I guess the world is going to start finding out about it. I have hid it for a while, because I didn't know what the reaction was going to be. It blew my mind so bad that I just kept it in.

Making this album is certainly the best way to let it out.

Well, I thought so.

It's a celebration—Jimmy Nalls is back making tremendous music.

Thank you—that's how I look at it.

Jimmy, is there some kind of deeper meaning to "Devil at My Door" and "Ain't No Stranger to the Blues?" Those are some pretty powerful songs there.

Well, "Devil at My Door" is obvious. I wrote that song the very month that I was diagnosed with the disease. I wrote it in about twenty minutes early one morning. I mean—bam!—I picked up my acoustic and my slide, and it was there. I had the tape machine rolling, I sang it through once or twice, and it was done. That doesn't happen very often with me—usually, I have to chip away at something. It's real evident what "Devil at My Door" is all about. You know though, it's cool—sometimes we all feel that way. Whether we believe in the devil or any kind of evil, sometimes life feels like you've got some kind of monster parked out on your door. You think, "Damn—is this ever going to leave me alone?" I mean, that's just part of life. Now, with "Ain't No Stranger to the Blues"—last summer, I had a particularly low point dealing with the situation, and the song is a result of that low point. Something positive did came out of it, and I think it is a very cool song. In hindsight, it reminds me of a Traffic song—the interplay between the piano and the bass and the guitar—everybody is just flat-out getting it, just groovin'. It's a bad song—right in the pocket.

It also reminds me a bit of "Midnight Pass" from Sea Level—just closing out so strong, everybody cooking.

That brings up an interesting point about this record—I don't know if people are going to be expecting an offshoot of a Sea Level record—maybe some people will. There was a killer instrumental track called "Tribute" that got axed from the project at the last minute that was really Sea Level, Allman Brothers style. Maybe it will surface later on, but it was a very, very cool song. I sort of tipped my hat to the whole Macon scene in the song, but it just didn't fit into what the album had become. It just broke my heart, but I was actually the one who made the call. I think people are going to be pleasantly surprised—like you seem to be—because they may be expecting more of a "Midnight Pass" or "Rain in Spain" kind of thing. There are just other aspects to my situation now.

Well, it's good to hear something new. I didn't know what to expect, and I love it. I really love the closer—"Jennifer's Wheel." It's real short, but it's so delicate, just fading out—it was the perfect way to wrap it up.

I'll tell you a quick story—that song got written at a T. Graham Brown soundcheck about six years ago. I started playing it, and the band sort of fell in, and we ended up playing that at every soundcheck. I was never able to write lyrics to it, and never able to finish it, but it was my daughter Jennifer's favorite song. She told me, "I really love that little piece that you do. Are you going to do it on your record?" I told her, "Well, the CD is about finished." She said, "Why don't you put a little bonus track at the end?" We went one step further, and we made it a real track.

When you open with "The Voo Doo in You" and close with "Jennifer's Wheel," it's a complete musical journey—and really enjoyable. Let's shift gears for a second, and talk about the old days. Sea Level—you guys made some of the greatest music to come out of Macon in the '70s, and now your first four albums are available on CD. For our younger readers—who need to get all four of them—which album do you think they should get first?

I think, for me, I would have to start with the first one, because it was just the four of us. That album had such a sweetness—but yet such fire—to it. It had so much fire—that's the only word I can use to describe it. Of course, the band evolved, with Randall Bramblett, Davis Causey, and Joe English, and so did the music. On the Edge is very cool, Cats on the Coast really rocked, and Long Walk had its moments. I love them all. I think the band started feeling the strain—an inward strain—you just reach a point where you saturate something, and I hear that on Ballroom, the Arista release. By the time we did Ballroom, I think most of us were ready to move onto the next phase of our lives, but it was great experience. I'll tell you what, man—that first run, when it was just the four of us—the interplay on that stage—we lit it up! Man, we were on fire—four guys getting out on that stage, with the people going, "What is this shit?" [Laughs] Then Randall and Davis bought a lot to the party—a large amount of material, and a real good vibe, but I gotta tell ya, I think the first album—Sea Level—is my favorite. I loved those days, and I still love all the guys.

Speaking of the Sea Level guys—in the last year, Chuck released his Christmas CD, What's in That Bag? Randall put out See Through Me, and now you've come out with Ain't No Stranger. 20 years after the fact, the Sea Level guys are back. It proves that there will always be room for great music from talented musicians.

I'm just so thrilled for Randall—I'm such a fan of his music. I love See Through Me—he and Davis did such a wonderful job on that record. When I play it in the car, it just nails me to the back of the seat. To be put in the same category with Chuck and Randall is very flattering to me—I'm honored.

The Macon scene in the '70s—you were a big part of that. Looking back, that period must have been a great time for a young musician like yourself.

It was heavenly, man—just a dream come true. Things like that only come around once in awhile, and luckily enough, I was able to play on just about every thing that needed an extra guitar player—whether it would be Gregg, Percy Sledge, Bonnie Bramlett, or whoever. I was friends with Johnny Sandlin and Paul Hornsby, and was luckily—and I thank God for this—part of that select group of guys that they were using. I was lucky enough to be one of them, and ended up playing on damn near everything that came through—even if it was just on one song—at least I got on there. Like Bobby Whitlock's record, Rock Your Socks Off—world's ugliest album cover—but I'm telling you, the playing on that will blister you. I keep telling the folks at Capricorn that they have re-released everything else—they really need to re-release that Whitlock album. That was just a wonderful time for me—looking back on it, you didn't realize how wonderful it was until the trip was over. When it did end, you just kind of went, "Man, that was really something." I'm glad to have been a part of it, even in some small way.

What are you thoughts on the future, Jimmy?

When you mention the future with me, unfortunately the first thing that I think about is my health, where an average person might think about their career. When I think of the future, all I'm trying to do is keep a positive attitude and trying to make music. I'm trying to stay busy, make music, and, above all, I'm trying to be a moving target!

Thanks Jimmy—God bless you.

|

|